Neoconservatism: A view from the rubble, part 2

The standard for optimism in Iraq is undergoing an adjustment that strongly resembles back-pedaling on our objectives. The proponents of the U.S.'s involvement are now pointing out, albeit less than sunnily, that civil war has led to many fine societies in the past.

There's a case to be made there. Think American civil war, English civil war, Thai Revolution in 1932, Japanese recontruction after WWII (not C.W., but a post-devastation success story). The WSJ editors take a stab at this argument but ignore most of the challenges presented by Iraq, instead recasting it as just another postwar civil reconstruction. One of the more interesting historical analyses of war as a gateway to peace and tolerance comes from Stephen Green at Vodkapundit, with this:

Christianity was a violent religion until the Thirty Years War. That war lasted so long, and killed so many people (the population of Germany was reduced by a third), that Christendom lost its bloodlust. Freedom of conscience was born on the battlefields of central Europe. The Middle East hasn't suffered that kind of loss; they haven't yet had their fill of blood; they haven't yet become disgusted with tyranny. I'd like to think that the Middle East can do what the West did, without all the suffering. But if it takes regional fratricide, then so be it.

But, as Green admits, there are plenty of instances where civil war leads to tyranny, authoritarianism, and continued, albeit quieter, bloodshed. Moreover, his optimism concerning the ultimate fruits of civil war (the rejection of violence and tyranny) fits along a trend of explanatory backfilling each time the empty promises, false predictions, and manichaean rhetoric of the administration fold under the weight of political realities in Iraq.

In the same way that you can't cure cancer with marathon training, it takes a rejuvenation of vital systems, and the absorption of managed stresses, to get a population to the threshold of political autonomy and self-correction. The hubris beneath the neocon ideal takes the form of misguided optimism that democracy is an incentive in and of itself, modeled to the envy of the oppressed everywhere by the U.S. But in reality, it is the security and prosperity that we enjoy in the U.S. that is attractive to Iraqis, and which will remain out of their reach because of the constant attacks and strong tensions, regardless of elections and attempts at a unified government.

Thus security is absolutely necessary to achieve the shared prosperity upon which freedom and stable government depend, but the U.S. did not go to Iraq expecting to have to actually provide that - encourage it perhaps, fund it, reward it, but not to build physical and economic security from scratch under constant attack. Is it safe to say we would never have gone, knowing the role that we were actually taking on?

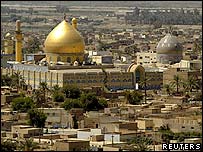

We entered Iraq knowing generally that democracy cannot take root in chaos, but inexcusably blind to the specific chaos that would result from eliminating Saddam's top-down containment of old ethnic hatreds. Concerns were met with a recitation of the misdeeds of the agent of that top-down containment, Saddam. It would be just like the cold war, they thought. Once we "disappear" the bad, the good (self-government) will rush in to fill the void. In fact, it was chaos in the form of ethnic tensions and violent opportunism from all sides, that was waiting to rush in, and did.

To the neocons, the lesson of the cold war was that democracy was synonymous with liberty, and that any oppressed population would embrace it, as if in a vacuum. There was no need to vet these theories. Iraq would be the vetting, and it would be successful. It was on this point in particular that the administration brooked no dissent, that the intelligence was most aggressively molded to fit the preset decision, and on which Cheney and Rumsfeld were intractable in the face of many gloomy assessments of the mission. It was a long-nurtured faith, and a desire to put this faith to the test, that kept them locked in on the long shot with no contingency plan but the comforting bulk of America's military and economic resources.

James Joyner, in his excellent and more objective expansion of Green’s idea, quotes Barbara Conry at the Cato Institute on the challenges facing foreign intervenors in an internal military conflict, i.e. civil war:

Intervening powers are at a disadvantage because their stake in the outcome is usually far smaller than that of the primary combatants.

In other words, the intervening force will not bring the necessary political will for victory to the project. The challenge is far more than just the political drag created by dissent within the U.S.; it is the whole fact of the detachment of the U.S. population from the site and the stakes of the struggle.

We will soon reach the point where it will be impossible to have any impact as an impartial force. Even assuming that the U.S. knows whose side it will take in the civil conflict, the war between the factions will not be arrested until they have reached exhaustion or one side has achieved dominance. The bad blood will continue, but at that point the opening for the establishment of a civil government will exist. The U.S. has neither the will nor the military means to cut short, or even manage to any significant degree, this conflict.

It may now become fashionable, at least in the political blogosphere, to shrug and point out the inevitability of civil war in Iraq, and indeed to portray it as a cathartic and necessary process. And the facts to support this view will exist. But if it is to be honest, this view must admit that every step up to this point has been built on the false presumption that democracy was not only an intelligible concept to the trampled, mutually suspicious Iraqi people, but an attractive one; not only that a three-way government could be propped up, but that it would sustain itself amidst constant sabotage by neighboring countries, each with its own claims on the allegiances of this or that Iraqi faction.

This raises a larger point about optimism in politics that I have been pondering, particularly since reading George Will’s column last Thursday, the topic of which was how conservatives tend to be happier than liberals. Will attributed this discrepancy to the general pessimism of conservatives, particularly to their low expectations of human nature. Under this view, surprises tend to be happy ones, while for the optimistic liberals, with their general presumption of altruism as at least a latent and desirable fact of human existence, life is an embittering procession of letdowns.

Optimism, commonly embraced as evidence of a cheery, can-do mentality, is often a cover for political deficiency, which itself is a precursor to inefficiency and tyranny. Both the American political left and right seem to each be most optimistic about, and take as given, those aspects of their agenda that most lack the substance or the wisdom to make them work.

Among traditional conservatives, such optimism is a sin and the mark of an unsteady, fallen soul (read: liberal). However, among neoconservatives, this particular prophetic, militarily borne optimism is a creed, premised on supposed truths far more esoteric than the human self-interest regarded by traditional conservatives as the foundation of government and social order. The neoconservatism's founding myth was derived from the (real) felling of the behemoth Communism, but its core message might have descended from Beowulf or St. George. And now, went the myth, all that remained was the triumph of mankind.

Links:

Robert Dreyfuss

digby discussing the Bush admin vis a vis Barbara Tuchman's criteria for historical folly